The number of foreign visitors is a good indicator of the event’s economic impact

CARLA MARIA ISSA

Senior Research Analyst, Property Finder

The upcoming year has quite a bit on offer; a couple of key nations will hopefully have a more progressive leadership by this time next year, and no, I am not referring to Bolivia or Taiwan. Additionally, the World Expo, the first to be held in the Middle East, will open in October and there is no better time to showcase Dubai and all of its advancements. In order to put this particular event in context, it is important to see how other cities have fared.

All of the world expositions, also referred to as world fairs, occur under the mandate of the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE). The BIE also organises specialised expositions, which occur in between World Expositions. Dating back to 1851, when the first World Exposition was held in the United Kingdom and Ireland, a total of 69 other expositions have taken place around the world. The United States has held the most expositions (12), with France coming in second, hosting nine events. Numerous others have been held in other Western European countries and increasingly in some Eastern European destinations such as Bulgaria and Hungary. Since the 1970s, Eastern Asia has held eight expositions, Japan (4), South Korea (3) and China (1). Most of these have been specialised expositions which occur every two years and have a different theme.

According to Ernst and Young, the Expo’s total contribution to GDP from the end of 2013 to December 2031 is expected to be AED 122.6 billion with the three most impacted sectors being: events organisation and business services, construction and restaurants and hotels.

World expositions and tourism

The Expos are important mostly because they are expected to rake in far more than the amount expended to host the show. Between an increased amount of tourists and the expected investments that should follow, what was once an opportunity to showcase culture has now grown into an important numbers game.

Generating tourism is one indicator for success. The highest number of visitors to any exposition was to Shanghai’s 2010 World Exposition, which attracted just over 73 million visitors, shattering Japan’s previous record in 1970 of 64 million visitors. Of those 73 million visitors, however, 5.8 percent or approximately 4.2 million visitors were foreigners, according to government data.

Another example was Montreal’s 1967 exposition which attracted 50.3 million visitors. This in particular was astounding as Canada at the time had a population of 20 million, with Montreal having three million residents. Unsurprisingly, the ratio of foreign visitors to local visitors has been the highest on record.

Japan’s most recent World Exposition in 2005 saw 22 million visitors, of which approximately 880,000 were foreign tourists. In 2015, Milan hosted the last World Exposition attracting 20 million visitors, 5 million of which came from outside the country. Although this exposition had aimed to attract 30 percent of foreign visitors, reaching 25 percent was a welcome statistic. Overall, Italy is the world’s third most visited country with over 60 million tourists per year and approximately 75 percent of Milan’s Expo visitors were either Italian citizens or day visitors.

The proportion of foreign visitors to the total number of visitors and the host country’s population is an interesting indicator of the economic impact the expositions have. Many cities go to great lengths to host the event in hopes that putting itself on the world’s stage will garner greater amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) and investment overall as well as contribute tourism spending for the hospitality sector.

Problematically, the turnout for some expos falls short of predictions. Toward the 2000 Hanover World Exposition, Germany invested $1.8 billion and predicted 40 million visitors. In the first six weeks of the six-month event, only 3 million visitors had come. In turn, the event’s managers had to lay off workers and slash ticket prices in a bid to ramp up the visitor count. By the end, only 18.1 million visitors had come through the doors, leaving the city saddled with a debt burden that ran as high as $600 million, one third of the total investment.

The most visited expo was Shanghai’s 2010 world fair, which cost the Chinese government $49 billion, approximately 8 percent of its annual gross domestic product (GDP) for the same year. For years prior to this exposition, the events had received much criticism for the sheer amount of investment they require, both on the part of the host government as well as the investment spent toward country pavilions by the attending countries.

In another example, the World Exposition held in Seville in 1992 cost Spain $2 billion, which included necessary infrastructure spending as well as spending toward pavilions. Another $10 billion was spent on urban improvements, including the construction of eight new bridges and a high-speed train that takes people from Madrid to Seville in just under three hours. When Seville’s exposition opened in 1992, the city had 25,000 beds in 3 to 5 star hotels and was expecting well over 50 million tourists. The city invented additional options such as hosting seven chartered Russian river boats that added an additional 2,300 beds as well as an additional 30,000 beds in bed and breakfasts and private homes. Within 45 minutes of the city, there were an additional 19,000 beds and another 22,000 within an hour of the site.

With the city seeing 40 million visitors, the majority of which were day visitors, supplying enough space for visitors to spend the night was not an issue. These number could lend some interesting insight toward Dubai’s Expo 2020 in terms of concerns over whether the available hotel supply versus the expected number of visitors will be too much or not enough.

Euler Hermes research found that in the case of Milan’s 2015 Exposition, the wholesale and distribution sector, hotels and catering, transport-related sectors and commercial services sector all saw an increase of between 1.3 percent to 4.2 percent year on year. Foreign direct investment, that is investments from a foreign entity which has at least 10 percent ownership, saw the inflow of €6 billion between February and April 2015, the highest quarterly figure since 2013. The report also notes that many of the businesses did well during the Expo itself, but were expected to face economic difficulties once the event ended. In Milan’s case, it was estimated that one company out of every 10 would be expected to go bankrupt before 2018, with many doing so in 2017, mainly in the construction sector.

When looking at the host city being able to accommodate the increased amount of visitors, STR, an American consultancy that tracks supply and demand for multiple market sectors, took a look at the Shanghai and Milan expos. In 2010, Shanghai had 192,000 available hotel rooms, although many visitors were domestic visitors, as approximately 200 million Chinese live within a two-hour drive of Shanghai. Of the 73 million visitors to the 2010 Expo, approximately 94 percent were domestic. During the Expo, Shanghai saw a 39 percent increase in demand, compared to the same period the year before. The average daily rate (ADR) during Expo 2010 was also 30 percent higher, as hotel operators inevitably increase their rates for the event, and by 2011 their rates declined by 26 percent. A year after the Expo, the city added an additional 11,000 new hotel rooms despite demand being flat after the Expo.

Some of the positive effects of Shanghai’s Expo were witnessed in the retail and residential property sectors, according to Colliers International. In anticipation of the event, the city remodelled a valuable chunk of riverfront property that previously was a long outdated shipyard and residential block. The property was redeveloped and sold to developers who transformed it into valuable retail and commercial property.

One of the most positive aspects for the city was the infrastructure it gained, including important transportation links and improvements to existing infrastructure such as an additional terminal at Shanghai’s airport. The city has also added numerous cinemas and cultural attractions, all aimed at keeping the Chinese happy and occupied.

On the world’s stage in 2020

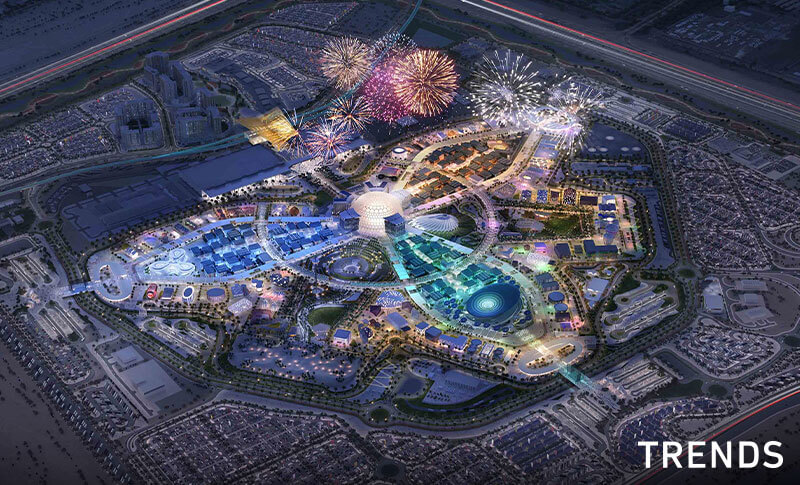

The Expo 2020 site represents a microcosm of the larger city around it. Dubai’s infamous “build and they will come” philosophy has generally yielded positive gains in the trade and transport space, helping it to become one of the world’s busiest ports, surpassing historically important trading ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp.

According to Ernst and Young, the Expo’s total contribution to GDP from the end of 2013 to December 2031 is expected to be AED 122.6 billion with the three most impacted sectors being: events organisation and business services (AED 68.9 billion), construction (AED 27 billion) and restaurants and hotels (AED 11.4 billion). The total investment in infrastructure and capital assets during this period is AED 40.1 billion. Of the expected AED 122.6 billion, AED 37.7 billion is expected to be gained in the “pre-Expo” phase of November 2013 through October 2020. The second phase, during Expo, is expected to gain AED 22.7 billion and the legacy/post-Expo phase is expected to earn AED 22.7 billion, with events organisation and business services (AED 54.2 billion), retail (AED 2.5 billion) and restaurants and hotels (AED 2 billion).

Considering the pre-Expo period is quickly drawing to a close, as much as AED 37.7 billion of gross value add (GVA), mostly from construction activities, will have already been absorbed in the economy. In total, AED 53.5 billion will be spent toward the event and the legacy infrastructure itself and the remainder is future anticipated economic activity that is expected as a result of having an increased profile for business and tourism at the global level.

The Dubai Statistics Centre and Dubai Economic Department both predict that 2020 will see 20 million visitors visit Dubai in total. Most reports indicate that 25 million visitors will visit Expo in 2020, which would yield an average of 145,000 visitors per day, every day for the duration of the event. Of the 25 million, 11 million are expected to be domestic visitors and another 14 million from overseas, many of whom will already be holidaying in Dubai and may set their sights on visiting the Expo for the day. Tickets will go on sale in March of 2020 and at that point, analysts will better be able to gauge visitor count due to these presales.

As 2020 begun, the vibe across the city already feels heightened, and I bet that feeling will increase in the months to come. Wintertime in Dubai brings a fresh perspective for residents and with the opening of the Expo in October and one year shy of the country’s 50-year anniversary, there won’t be a more exciting city to be in than Dubai.

Sources: New York Times, Ernst & Young